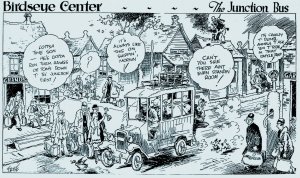

Birdseye Center by Jimmy Frise.

Jimmy Frise (1891-1948) was the most important Canadian cartoonist of his time, the creator of two cherished comic strips, Birdseye Center and Juniper Junction. Although he was among the most widely-read Canadian creators of the early 20th century, Frise’s work has largely been forgotten, a real injustice since his lively linework can still raise a smile. (For samples of his work, go here.)

During the Doug Wright Awards last month, Frise was inducted into the into the Giants of the North, the Canadian Cartoonist’s Hall of Fame. It was a moving ceremony with one of Frise’s daughters present, along with a strong contingent of grand-children and great grand-children. Storyteller and broadcaster Stuart McLean, whose homespun humor on the Vinyl Cafe show continues the tradition started by Frise, delivered a speech on the cartoonist and his work.

Here is a text of what McLean said:

Canada was still a hinterland nation when Jimmy Frise was born in 1891 on Scugog Island, Ontario — a small community just a crow’s flight north of Toronto.

Frise’s hometown was typical of Canada at large; A broad nation of farms and villages, tank towns and railway junctions, where most people still lived off the land.

Fifty seven years later, when Frise died in 1948, Canada— its mettle tested through two world wars — was well on its way to being a modern, urban nation with its citizens congregating in big cities and doughnut suburbs near the border.

In his life and cartooning, Frise served a bridge between these two competing Canadas of the early 20th century—the homey rustic land of his childhood and the bustling metropolitan nation that emerged as he grew into adulthood.

In his long-running and much-loved comic strip Birdseye Center, Frise perfectly evoked, with mildly teasing good humour, the Canada of his youth.

With its rural setting and large cast of eccentric and slightly exaggerated characters, Birdseye Center was the perfect memorial to Scugog and its environs. But if Frise was constantly looking back to his childhood, he did so with the slightly ironic eyes of a cosmopolitan adult—a worldly newspaperman who could handle his own in bars and gambling dens.

Growing up on his parent’s farm near Scugog Island, Jimmy Frise taught himself to draw. Newspaper comic strips were taking off just as Jimmy hit his teen years and through newspapers like the Toronto News and the Daily Star, he followed the adventures of Buster Brown, Little Nemo and the Terrors of the Tiny Tads.

In 1910, Jimmy moved to Toronto where he landed an entry level job for the Canadian Pacific Railway, drawing maps of farm settlements in Saskatchewan. Since all the lots he had to draw were nearly perfect squares, the job basically required a firm hand with a ruler.

Living in a rooming house, Frise dreamed of breaking into newspaper illustration, but he had no contacts nor any leads. His big break came in November 1910 after he read an exchange in the pages of the Toronto Star between an editor and a farm hand; both men claiming that they could do the job of the other better.

With his memories of farm life still fresh in his mind, Frise dashed off a quick light sketch that summarized his thoughts on the matter. The cartoon, which humorously contrasted a bewildered editor attempting to milk a cow with a farm hand looking flummoxed behind a typewriter; Frise submitted the drawing to the Star.

But unaccustomed to the ways of freelancing, Frise neglected to include either his name or return address. The Star published his drawing on November 12 anyway, and when the aspiring cartoonist showed up weeks later to claim his fee, the editor hired him on the spot.

In his early years as a staff cartoonist, Frise popped up in nearly every nook and cranny of the broadsheet, producing everything from political cartoons, to spot illustrations of news events, and even nature drawings for the children’s feature The Old Mother Nature Club.

Frise’s style at the time was certainly competent, but uninspired. His early characters like “Jonnie Canuck” was a goody two-shoes boy scout, and “Miss Canada” a rather bland maiden. It would take a World War to solidify his style into one Canadians would grow to love.

Joining the army 1915, Frise served in the 12th Battalion and fought in the critical Canadian battle of the Great War, Vimy Ridge, where he lost part of his left hand (fortunately her drew with his right).

It’s a measure of Frise’s sangfroid that while convalescing in England he drew a cartoon depicting the pleasures to be found in a military hospital, complete with comely nurses on hand.

During his war years, Frise’s drawings underwent a major change: Instead of faithfully trying to replicate reality, they suddenly started bubbling over with personality as he began giving a comic spin on events. The war made Frise much more confident, so he could now use cartooning to openly express his worldview.

The war also made Frise more serious about his personal life. Almost immediately upon returning to Canada in November 1917, he started courting Ruth Elizabeth Gate. They married on February 21, 1918. The couple had four daughters and a son, and many grandchildren, some of who are here tonight.

Now a family man and secure staff job at one of Canada’s largest newspapers, Frise was ready to start his major life’s work. But Birdseye Center wasn’t born in a fit of inspiration — it slowly emerged out of Frise’s work.

In 1919 he started doing a one-panel feature called Life’s Little Comedy. Inspired by the observational sketches of W.E. Hill, Life’s Little Comedy showed scenes of everyday life in Toronto: one strip focused on the ice rink as a locale for dating, another showed how office workers used lunch time to play pool or take in a quick movie.

But by the early 1920s, Frise started to do more and more strips about rural life. He found more pleasure in dwelling on comic memories of Scugog Island rather than the Toronto he lived in. Or more precisely Frise, knowing full well that Toronto was full of erstwhile farm kids like himself, found it funny to look at the oddities of Scugog through the slightly bemused lens of the city dweller. Within a few years Life’s Little Comedy transformed into Birdseye Center.

What made Birdseye Center a great strip was Frise’s gift for character creation. His cast of characters, all limned with his loose scratchy pen-line— often feathery and ruffled around the edges, were a splendid crew of eccentrics. Favourites included Old Archie and his wife Emmy, whose pet moose Foghorn was a reliable local nuisance. Then there was the lazy goldbricker Eli Doolittle (aka The Fattest Man in Town) who was reluctant to do a lick of work except when it would encourage his in-laws to decamp the from his house.

And there was Pig-skin Peters, arguably the most popular of Frise’s extended family, a pie-eyed bachelor and roustabout that stood out thanks to his striped shirt and derby hat. Pig-skin Peters was so popular with readers that in the 1940s Canadian football fans started to don his attire during games between arch-rivals Toronto Argonauts and the Hamilton Tiger-Cats. In fact, this practise continues to this day at Hamilton Ti-Cats games, where “Pigskin Pete” serves as an official morale booster for the team.

Birds-eye Center was a bonafide Canada-wide hit, appearing in newspapers from coast to coast. Frise’s fame was augmented by his collaborations with his old friend Greg Clark, the newspaperman and storyteller. Every week Clark would write a story about various misadventures he and Frise had while hunting or fishing. Frise not only participated in these tall tales, he also illustrated them with beautifully composed full-colour drawings.

The comic team-up between the writer and artist worked like a charm, even to the point that the two men physically complimented each other. Clark was as short and stocky as Frise was tall and languid. The two men played off each other like Laurel and Hardy.

In 1947, Frise was at the height of his fame when he made the final big leap of his career moving from the Toronto Star to the Montreal Standard. In the process he changed Birdseye Center into a full-colour Sunday strip called Juniper Junction (the name change necessitated by The Star’s ownership of the title Birdseye Center). For the first time, his strip started appearing in American newspapers. When the heart attack struck the following year, it killed a man still bursting with creativity.

The word most often used to describe Frise was “gentle.” “Jimmy was an original,” Greg Clark remembered. “Unbendable, bemused, rapt, lovable guy in love with the gentleness and decency of life amid all the storm and rage.” His notorious charm and grace even won over a green cub reporter named Ernest Hemingway, who landed at the Star after the First World War and immediately glommed onto Clark and Frise – even tagging along on fishing and hunting trips with the cartoonist. Decades later, the news of Frise’s untimely death would prompt Papa Hemingway to reconnect with Clark from his hotel in Havana. The author opened his 1950 letter by acknowledging Jimmy’s death, writing “That word ‘late’ is one that I could just about do without.”

If Canadian cartooning is viewed as a family tree, then Frise was the trunk: the pivotal 20th century figure who proved that comics could mirror the everyday life of ordinary Canadians. Out of Frise’s work grew many branches, including the work of Doug Wright (who took over Juniper Junction, drawing the strip from another two decades) and Lynn Johnston (whose suburban comedy can be traced back to Frise’s rural roots).

Jimmy Frise was the most important Canadian cartoonist of his time, and his work deserves not only to be remembered and honoured but also collected and re-read. He told the story of Canada with a wit and verve few artists have possessed.

And for this reason we are pleased to induct him into the Giants of the North; Canada’s cartooning hall of fame.

I have two Jimmy Frise cartoons , which were published in Standard newspaper in 1947 . These cartoons both have date and signed by Mr. Frise , my question is where can I get them appraised , they are both watercolors and in perfect condition {Juniper Junction} Thank you for your help. Dan Laing

Mt Laing – Feel free to drop me a line at mackbrad at gmail dot com.I think I know someone who can help you out with this.

Great article, thanks. Mark Frise.

I AM A SENIOR MALE WITH A HILARIOUS IDEA FOR A CARTOON : cARRICATURE OF kIM sOON WITH A ROCKET AND A GOLF DRIVER STIXCKING OUT OF HIS KNAP SAK AND TRUMP ILLUSTRATION WITH A MACHINE GUN DRAPED OVER HIS SHOULDER MARKE nra ON THE MACHINE GUN AND ILLUSTRATING THE LOCATION OF THE PEACE TALK AT tRUMPS fORIDA HANG OUT MY EMAIL IS morrisz@rogers.com